What’s In A Name?

By user • Mar 26th, 2011 • Category: Diary

The following is an excerpt from a forthcoming collection of short stories about living abroad in Taiwan.

Call me American.

Everyone else does, some way or another.

If you’re speaking Mandarin Chinese, it’s “Měiguórén.” To more than a billion people, my nationality sounds like Elmer Fudd on a Rogaine bender. “It may gwow in, it may not gwow in.”

In Indonesian – the language I suffered through while diligently trying to graduate college along the path of least resistance – it’s, “orang Amerika.” As in, “American orangutan.”

It’s “Amerikaanse” in Holland; “Américky” in Czech Republic.

To South Africans, I’m “Amerikaner” – the same as to the Germans – but only when speaking the hybrid language of Afrikaans. Otherwise, it’s back to simply “American,” but in that portentous way Saffers drag out short “A” sounds as though they’re battling a stingy yawn. The French elongate a couple of vowels, too. “Américain.”

In Finland, I’m “Amerikkalainen,” but “Amerikietis” in Lithuania. Despite never skiing a downhill slope in my life, the Polish give this “Amerykanski” the benefit of the doubt. The Spanish, Italians and Portuguese say, “Americano,” which is perfectly suitable for a delicious coffee, although not too fitting for a tall drink of water like myself. To the pun-happy English, I might be “American’t” – or, possibly, “Americunt” – depending on how far their posh meter sits away from the red.

If given a choice, I’d opt for you to call me “Ishmael,” or, at the very least, “Al.” Even after living in the country for almost three decades, “American” takes some time to warm up to.

That’s because I never had been “American.” I’d been a Yankee. A Midwesterner. A Chicagoan. I’d been a city slicker and a suburbanite – simultaneously – depending on who was asked. I had been any number of geographical descriptions, just never “American.” That was too easy. It was too obvious. The United States is full of “Americans.” Being another in the crowd was nothing special, especially when overzealously embracing those roots gets left to brazen patriots via bumper stickers, T-shirt slogans and country music.

Chalk it up to my general lack of national pride. Call it an insatiable quest for something new. Write it off as blatant naivety. I may never know the full truth behind my decision to uproot this American life, to leave the print media, end my talk-radio program, sell off my belongings, box up my comic books and CD collection, and put an ocean between me and my loved ones. But that’s exactly what happened when Amy and I abandoned everything we knew Stateside and moved to the island of Taiwan to teach English.

I was 28 years old going on dead. I wasn’t young enough (or old enough) to think I knew everything, but I was fairly certain that my window for real cultural significance was closing quickly.

That’s because George Harrison was just 27 years old when The Beatles broke up. Kurt Cobain died at that age, as did Brian Jones, Jim Morrison, Chris Bell, Joseph “The Elephant Man” Merrick, Robert Johnson, Mia Zapata, Pope John XII, Jean-Michael Basquiat, Amy Winehouse and Janis Joplin.

At age 26, Albert Einstein published the theory of Special Relativity, which lead to discovering later the same year that E=MC2. That’s also the age that Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg had his net worth estimated at $6.9 billion.

Orson Wells peaked even younger – at age 25 – when he wrote, directed and starred in Citizen Kane. Alexander the Great did so earlier still, when he conquered Persia by age 24. That’s how old Duane Allman, Joan of Arc, Lee Harvey Oswald, The Notorious B.I.G. and James Dean were when they died, but a year older than Ian Curtis, who hanged himself at age 23. Coincidentally, 23 is the age when Pablo Picasso ended his Blue Period and that Rivers Phoenix overdosed.

By 22 years old, George Washington already had led the military siege of Fort Duquesne. Buddy Holly, however, wasn’t so apt for survival; that was when he perished in a plane crash.

Sid Vicious and Eddie Cochran both died at 21, the age that Elvis Presley made his national TV debut, although The King’s groundbreaking Sun Studios material was recorded by age 20. Those seminal sessions were cut at the same age that boxer Mike Tyson later would become the WBC heavyweight champion of the world.

My 20s, on the other hand, had been a decade spent living on chump change, coffee grounds and ego boosts as a music journalist. The biggest obstacle I faced growing up was that I came from an affluent area with hyper-supportive parents. It’s hardly the ramshackle upbringing that writers tend to romanticize. And nobody ever has put a rock ‘n’ roll critic on a shortlist of important people – not even Lester Bangs.

So I became “American.”

Like many fellow countrymen, my mutt ancestry is stirred together like an improbable gene cocktail. Half mad scientist’s potion, half drunk bartender’s after-hours special, it’s a legacy that feels a bit like a dare to mix nationalities to see what happens when the combustible result is aged then served on the rocks. My mother’s family hails from Ireland. We know because an aunt spent 15 years tracing leads to be sure, but proclaiming a Dublin lineage each St. Patrick’s Day hardly makes an Irishman. That same research into our family tree uncovered a wealthy relative who suffered a nervous breakdown and spent the Great Depression hiding jewelry inside market bread loaves, another relative who died of infection after having his testicles shot off during the Civil War, and a third dubious ancestor who took occasional summers vacations to Al Capone’s Floridian home.

So consider the source.

Ask my family directly about our supposed homeland, and the answers range like RISK battle plans.

“Ireland.”

“Germany.”

“Yugoslavia.”

“Czechoslovakia.”

“Poland.”

One cousin swears that we’re “half Irish, one-quarter German, one-quarter Czech, one-quarter Polish, one-eighth Russian and one-sixteenth Jewish, … or something.” When pressed on how we inherited such a knack for arithmetic, he assured me, “Grandpa spent time in Korea, but that doesn’t make us Asian.”

It does make us 143.75 percent confused, … or 100 percent “American.”

The United States is a nation filled with people searching for an identity who want so desperately to be from somewhere else that we cling to every hint of tradition. When asked about heritage, we instinctively cite from where our parents or grandparents emigrated without a moment of guilt in the exaggeration. If that doesn’t turn up something unique, we reach back to great-grandparents, or great-great-grandparents, or whatever generation hopped on a boat and battled weeks at sea to be greeted at the Statue of Liberty by Emma Lazarus’ plea for “your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

It’s a slogan as empowering as it is crippling. It has reminded generations that they live in America because their ancestors weren’t a good fit elsewhere. Instead of joining citizens as “American,” this petition to recall international ancestry has built a nation quick to spot the differences among one another. We’ve learned not to embrace the remaining similarities, but rather, ways to point out how “not like you” we each are.

It’s seclusion mistaken for inclusion – a divided nation masked as a diverse one – and Americans might be the best in the world at turning something wonderful into something toxic. As we haplessly dig for individual roots, we chop down hope of unity. “You and I might be from America, but my ancestors once fought under King Phillip II, and yours later saddled up next to Napoleon, so we have a lot less in common than the rest of the world thinks.”

My Brazilian friend, Pedro, once confronted this. He is a true Brazilian, born and raised in Rio de Janeiro, living in São Paulo, and with enough Latin charm to woo the pants off a marble statue when he isn’t spending afternoons donning a Pelé jersey and offering tourists free waxes during Carnivàle.

“I’m Irish,” I told him over a late-night drink.

“But you’re from Illinois,” he said.

“Yeah, but my family is Irish,” I distinguished.

“You don’t have an Irish accent.”

“Oh, I never lived in Ireland,” I explained. “My family is Irish. Look, I have a Celtic tattoo around my ankle.”

“But you’re American,” he said, perplexed.

“My family is from Ireland, but, yes, I’ve always lived in America.”

“When did your parents move from Ireland?” he innocently pried.

“Actually, my dad was born in Germany on a U.S. Air Force base.”

“But you’re not German.”

“No. My dad was born there, but on a U.S. military base,” I theoretically clarified.

“So, you’re dad was born in Germany, …”

“On land issued to the United States,” I interrupted.

“And you’ve never been to Ireland, and neither of your parents lived there?”

“I’m a U.S. citizen. I have a U.S. passport. I’m not sure when my relatives came to America. My parents, grandparents, my great-grandparents, their parents, …” I trailed off.

“How are you Irish?”

“Well, my family is, …”

“American,” he said conclusively. “You’re American.”

His logic was linear and flawless. My line of reasoning meant anyone subscribing to the Out of Africa theory could call themselves African, or that the staunchest evolutionists could claim to be self-replicating RNA. It was a slope greased with confusion and slipping toward utter delusion. If I were anything, it was American, for better or worse.

Living in Taiwan confirmed that almost daily.

It’s a phenomenon that I had been warned about indirectly many years earlier. While taking an international communication course in college, my university’s women’s basketball coach offered a lecture. She had spent time playing professionally in Japan, and the professor asked her each semester to relay the experience of working overseas. Tucked among anecdotes about sleepless nights was a statement of pride.

“People didn’t judge me for being black, or female, or 6’4” tall, or athletic or smart,” she recollected. “If they judged me, it was as an American. None of that other stuff mattered. To them, I only was American. It’s the most patriotic I’d ever felt.”

The categorical adjectives used to marginalize citizens within U.S. borders don’t matter abroad. By overlooking ways that so many others had defined her back home, people saw who she was in the simplest of terms: one person from America. Any subsequent judgments came after she had the opportunity to make a personal impression. “American” is a blanket tossed over anyone from the 50 states. That’s who we are.

Upon arriving in Asia, I initially described myself as being from “just outside Chicago.” But the translation of “outside” meant a great deal of time clearing up confusion that the city didn’t have a literal front gate. I quickly opted for saying “near Chicago,” and then “Chicago,” which is equally as worthless of a geographical indicator. Any Illinoisan with an inferiority complex following the 2016 Olympic-bid fallout needn’t bother seeing exactly how much the city is a global afterthought. Peruse the U.S. Travel section in Asian bookstores, and you’ll shuffle through numerous New York and Los Angeles guides before maybe finding one Windy City handbook.

So I embraced “American” and appreciated the ease that followed. It didn’t mean lengthy discussions about foreign policy, nor did it come laced in contextual undertones or spark philosophical debates about what it meant to be one, as I had feared. “American” was a matter-of-fact description no different than “right handed,” “tall” or “bald.” It was something that, … well, … just was, by default. To the Taiwanese, it was the fastest way to distinguish me. To foreigners, it didn’t require speaking on behalf of my countrymen or imply flag-waving patriotism. I was “American,” which is different than being “an American.”

The only people who demanded further explanation were fellow Americans. Saying, “I’m from the States” sufficed for Canadians, Taiwanese, Australians, and most nationalities. But leave it to U.S. citizens to need segregation. “Oh really?” they’d so often reply. “I am, too. Whereabouts?” Instead of embracing the similarity of our situations – foreigners living in Taiwan – we defaulted to chopping through to find what made us different, to revel in how little, not how much, we had in common.

Thus, when meeting others, I made a point not to care – rather, not to ask – from which part of the country they came. If they were like me, they’d be on heightened alert against being judged on nationality; the last thing needed was a fellow Statesman sending them into attack mode to combat stereotypes attached to specific U.S. regions.

It didn’t matter whether Jared from Missouri bled St. Louis Cardinals red. (Even if the Chicago Cubs fan in me wanted to know). I didn’t care whether Daniel from Portland spent his days eating granola, listening to Elliot Smith and dissecting poetry. It was unfair to assume that Tyler from Texas had wasted his afternoons barbecuing homegrown cattle. My quartet of friends from Seattle didn’t seem like the type to admire rainy afternoons while contemplating joint suicide over coffee luncheons. Just because friends from California’s bay area loved sandals, it didn’t mean they spent weekends back home surfing and pining over Gilman Street. Alex from Wisconsin probably hadn’t been groomed on a diet of sausage, cheese curds and beer. Well, … actually, … he probably had been, but it didn’t matter anymore in Taiwan. We all were “American.”

It didn’t take long before I began referring to everyone that way. Foreign friends like Maurice, Robyn, Tarryn, Darius, Esti, Brynn and Kath weren’t South Africans; they were just “South African.” Alan wasn’t a Scots – even if I did occasionally ask him to recite passages from “Trainspotting” – he was “Scottish.” Andrew and Phil weren’t Englishmen; they were “English.” When I wanted to annoy them, they were “British.”

I would have been hesitant to use this verbiage before living abroad in fear it implied a belief that every person from a country was interchangeable. But making the distinction that I was “an American” instead of “American,” suggested that whomever was on the other end of the conversation was ignorant enough to think all Americans believe, speak, vote, and act in unison. It became redundant to distinguish a defiant sense of individualism between oneself and country. Apart from a few aptly named people in countries like Chad, Jordan, and Georgia, citizens don’t define their nations, nor are they defined by their nationality. Only a fool fails to see that.

Being “American” was a matter of fact, and there was no reason to fight it.

Besides, there are plenty of worse things to be called, and sometimes those worse things are people’s names.

In most language classes, children are asked to pick an alternate name to add authenticity to their studies. When learning Spanish in elementary school, I went by “Santiago.” In junior high, I switched to “Tupac” after convincing the teacher that it was a common nickname among villages in rural Venezuela, despite being fairly unheard of in Mexico.

It’s the same for English-learners in Taiwan, and these Western names are more for teachers’ benefits than the students’. In some cases, they come with a great deal of forethought. One coworker’s given name was Líng Yī. When spoken in the correct tones, it sounds like the Mandarin Chinese words for “zero one.” As a result, her English name became the similar-looking Zoe.

In other instances, however, they sound like a joke to see how long before someone bursts out laughing and questions the sobriety of the people involved in the naming. An advantage of teaching the youngest possible students is the chance to join in this process. Often, kindergarten students are too young to have an English name, and teachers help select what the students will be called. It’s like experiencing one of the perks of expectant parenthood 30 times every six months.

There’s no harm in naming the cutest girl in class after Mom if you’re feeling a bit homesick. If a pupil is reminiscent of a childhood best friend, why not pass his or her name along? Always wanted to be called something else? No shortage of students to dole out the many names you’ve fantasized about.

There’s a lot of pressure that comes with choosing a person’s name. My freshman college roommate and I bought a beta, and took three weeks to settle on calling it Rivers. The fish died about 48 hours after we agreed upon the name. It can’t be a coincidence; and that was an animal without a neocortex that was dumb enough to fight its reflection.

One of my school’s upper managers recalled a naming fiasco that she faced when she started teaching on the island, long before being promoted out of the classroom. During her first year in Taiwan, she inherited a classroom of revolutionists. The previous teacher had given students names such as Lenin, Marx and Medusa. Her first act was to rename the entire bunch, which was met with historically accurate little resistance aside from one family. Their boy, Stalin, had been rechristened Matt. However, his parents’ dictionary only listed “mat,” as in the verb meaning “to tangle” like dirty hair. They weren’t pleased with the translation and demanded it be changed back.

My classes luckily were devoid of polarizing Russian leaders but not of unusual names.

Boys who sounded like pirates (Bluke, Kenbo) and superheroes (Liquify, Spark, Quantum, Rock, Alpha) sat alongside girls who sounded like strippers (Bambi, Barbie, Candy, Kiss, Queenie). There was a “Top Gun” fighter pilot (Jester) and a painter (Picasso).

There were those that felt hopelessly optimistic (Win, Luck, One, Victory, Angel, Prince, Smile, Cash) and some that were downright unfortunate (Dorkus, Lucifer, Ninni). Some were forces of nature (Wind, Rainie, Ocean, Sunshine, Snowflake, Floral), while others were lifted from their parents’ day planners (March, April, May, June, August).

There was a male Kimi and a female Ian, and plenty of foods (Apple, Soup, Cherry, Strawberry, Kiwi).

Then there were the animals (Eagle, Tiger, Kitty, Cheetah, Fish, Whale). One student hated her birth name because of how similar it was to the Chinese word for “rabbit,” yet adored her English name, … Bunny. Another girl was called Squalo, which isn’t a name at all, but does mean “shark” in Italian.

Class rosters ran the Disney gamut, from princesses (Jasmine, Ariel, Belle), to celebrities (Mickey, Donald) to villains (Ursula, Ratcliffe).

In a stroke of dumb luck, a single class featured Wei and WeiWei, Casper and Casber, and Lulumi beside her twin, Lulumimi. Another class had a Fiona, Fion and Fi, but Ona was in a separate class. Jack sat next to Jill; Bill was seated near Ted; and a third hellish class had both Hades and Persephone. Fittingly, there were two talkative students named Echo; a girl named Button who was as cute as one; and a quiet, boring girl named Prairie. There even was someone named Ting, whose meek demeanor left her hanging on every word, and whose name appropriately translated from Chinese as “to listen.”

Every teacher has stories about a friend of a colleague who taught a Young, or a Christ, or a Dude, or an M&M. Some names seemed reserved for the smart students (Angus, Vivian), while others curiously always fell to rude ones (Derek). In one class, Ben and Benny were shocked when told that they shared a name; siblings Jim and Jimmy refused to believe as much. Then there was Joshua. Regular, plain Joshua, who decided one day that he’d respond only when called “Super T-Rex.”

That’s the thing about these alternate names: They were subject to change because they mean very little in day-to-day life. They exist for the classroom and for when Taiwanese people deal with foreigners. Among one another, these names are virtually useless. Often, students don’t know what their best friend is called in English. One coworker was uncertain of her husband’s English identity. It was a jarring moment when Amy and I realized that we didn’t know the actual names of the students and colleagues whom we saw daily. We knew their temporary names but not their given ones. Not the ones that mattered to them.

The Taiwanese can have as many aliases as a KGB agent. One coworker, who had been called Vicky since childhood, was asked upon being hired to take a new name because another Vickie already worked in the office. Having two would be more confusing, apparently, than getting renamed in her mid-20s. A second coworker, Apple, informed everybody one afternoon that she had decided to ditch the pome and become Gabriel. The only people who found this strange were expats. The school’s Taiwanese staff members took the change in perfect stride.

For Westerners living in Asia, however, alternate names are far more than vanity. Whereas a Taiwanese person’s English name is an item of convenience, foreigners are required to take a Chinese name for legal documents. These can’t change on a whim, and in most cases, a native citizen selects them without outside input. That’s to say, we get what we’re given.

These are chosen much the way that Chinese students take English names.

One option is to find a Chinese name phonetically similar to the Westerner’s birth name. Amy’s, for example, became Ài Mǐ, with almost identical pronunciation. My name, Derek, became Dà Ruì.

Another option, however, is to find Chinese names with proper meanings. A loose take on Amy’s new name is “love meter.” A more literal translation means “love rice.” She is tiny, and does have a pasty-white complexion. My name translated indirectly as “big farsighted” and directly as “big astute,” which might have been derived from something like “big head,” … or “big hairline.”

We hoped our Chinese names were based in phonics and not appearance.

A fellow foreigner’s new name meant “awesome dragon,” and another’s was the slang phrase for “goddamnit.” But, still, there are worse things to be called than accidental curse words.

Among a list of four-letter expletives is a three-letter one: “LBH,” short for “Loser Back Home.” Dylan, a teacher from New Zealand who’d worked in Japan and China before Taiwan, introduced the phrase into our vocabulary. The term was reserved for socially awkward, misogynistic Western men who travel East with the goal of marrying a gorgeous Asian woman, … or just sleeping with as many of them as possible.

It’s a volatile term not uttered lightly because it’s a conversation ender. For foreigners living abroad, there are few insults worse. And there was no shortage of LBHs in Taiwan.

A common misconception – one propelled by Internet forums and barstool braggarts – is that the relationship dynamic in Asia is opposite that of the West. The myth is that women in countries such as America and England control how quickly a physical relationship develops, but Asian females all secretly desire to get plucked off the street at any moment by a catcalling foreigner.

Men who subscribe to the idea of submissively sexual Asian females flock to countries such as Taiwan, spew a few English phrases, and expect to have attractive women fawning with dreams of a Western husband. These guys – LBHs – are easy to spot. Their motives are as transparent as the lace miniskirts they’re drawn to. They parade ever-changing girlfriends through a revolving door of commitment, carefully avoiding talks of the long-term with just the right amount of foreign mystique to seem heartfelt.

Not all men who date Asian women were losers back home, and one conversation with a Taiwanese woman should dispel the notion that they’re shallow, flirty girls with an obsession for all things cute. One of my dearest friends in America met his wife while stationed in the Philippines with the U.S. Navy. Two children and almost three decades of marriage later, there’s no doubt that his relationship is genuine. But a great number of men do act as though effortless sex with attractive Asian women is an entitlement of speaking English overseas.

The LBH occurrence is so widespread that it spawned the Japanese comic strip Charisma Man. It tells of a Canadian guy who traded his life as a geeky fry cook for the role of a suave, womanizing traveler. His nemeses are Western women, the only ones who see through his cocky demeanor abroad to detect his pathetic roots. It’s much like the kid from high school who enrolls in out-of-state college, starts calling himself “David” instead of “Dave,” grows a goatee, and gets an eyebrow ring in hopes that nobody will realize he’s the same person who used to eat glue and shower fully clothed after gym class.

LBHs keep everyone on edge.

Taiwanese women are left wondering whether all foreign men have selfish intentions, so they pick their friends carefully. Taiwanese men, in turn, are protective of female friends, cautious of their interracial dating, and cold to foreign boyfriends. Western women speculate their significant others secretly harbor the LBH gene and worry it’s only a matter of time until it’s unleashed. They distrustfully warn their spouses against making friends with Asian women. Thus, goodhearted Western men are kept on the defensive, perpetually asked to invalidate wives and girlfriends’ fears of a loser back home, always having to prove they’re not interested in frivolous sexcapades.

One thing about LBHs, is that there’s little doubt about motives: They keep one eye on their bar tab and the other on the nearest waitress. Like any sect with low self-esteem, they’re woefully aware of their own faults. One common idiom is to “call a spade a spade.” William Shakespeare wrote, “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” Popeye proclaimed, “I am what I am, an’ tha’s all I yam.” Dylan’s phrasing came a tad less poetically. “They like beer. They like sex. They’re in Asia,” he surmised.

When put so bluntly, LBHs seem to be sufferers of their environment almost worth pitying. With the right PR spin, their solo move around the globe becomes admirably brave, not a cowardly trip for thrills without consequences back home. Nights on the town become searches for a companion, not predatory hunts for a warm body. It’s all about perspective, and it boils down to whether the one-night stands veiled as long-term relationships are the results of or reasons for moving to Asia.

The world may never know, nor should the world care. There’s glamour to minding ones own business in posh isolation, not in ignorant bliss. Living as “American” had taught me that. How we label the world matters very little – even less than how the world labels us – and neither truly compare to how the world … is.

That’s especially true as I found myself living in a place that portrays America as a giant wild-west town. Not all Taiwanese viewed America in such a way, but the members of the Taipei City Government did during my first Lantern Festival, which they put on vivid display.

Lantern Festival is one of Southeast Asia’s most celebrated times. On the fifteenth day of the lunisolar year, people throughout Taiwan, China, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and the region flood streets, parks and the sky with elaborate lights. The tale of the holiday’s origin varies in each country, but festivities nonetheless date back centuries and have evolved over generations into a weekslong spectacle. Wishes are scrawled on sky lanterns, which are sent floating toward the heavens over the stationary exhibits that attract onlookers by the tens of thousands. Family elders regale children with stories steeped in their heritage, while the youngsters battle timeless riddles. Homemade food, music and art are blended seamlessly into large, commercial showcases.

In Taiwan’s capital, a lengthy parade escorts the works to their annual resting positions. Floats are constructed as fully functional lanterns, illuminating the roadways before settling in a memorial park where they glow for the duration of the holiday. The festival grounds are divided by themes. During my first year, they ranged from “The Wizard of Oz” area to the “Praying Lantern Zone,” which housed floats dedicated to stuff presumably in need of prayer, like “health,” “peace,” “love” and “children.”

One area, “The Five Continental Lantern Area,” coincided with my new embrace of “American,” with luminescent depictions of Europe, Africa, Asia, Oceania and America. Each territory was given its own float, and the festival’s booklet invited patrons to “Welcome to experience the dreamy and happiness here.”

The park’s walkways were packed with tourists and locals standing shoulder-to-shoulder amid a pale, fluorescent glow. Bulbs of every shape and color adorned the numerous floats, putting off an inspirational mix of light. Vendors sold glow sticks, bracelets, masks and souvenirs, each brighter and more intricate than the last.

As Amy and I weaved toward America, we strolled passed the Asia float. Sandwiched between a mosque and a temple was a panda riding on the backs of two tigers, … over cherry-blossoms, … and through a bamboo forest. It sounds like the start of a racist joke. “A panda and a tiger walk into a temple, …”

Then we saw Africa. A lion and a camel dodging a spear … in front of the Sphinx.

Oceania featured a koala nestled in a kangaroo’s pouch, while a herd of sheep grazed at the base of the Sydney Opera House.

Then we passed Europe. A pair of beefeaters stood guard in front of a windmill, while a small girl took a break from watering roses and tulips to slip off her wooden shoes.

“What is that?” barked our friend, Andrew, in his Mancunian accent as we faced his homeland’s Queen Motherless float. “What shit!”

I felt united in his confusion as we turned toward the America float.

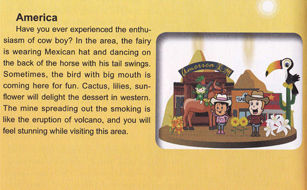

On its right side, a toucan rested atop a Saguaro cactus. On the left, a small boy wearing a sombrero danced the Meringue on horseback. Its backdrop included two dusty mountains speckled with golden nuggets behind a rickety, wooden saloon that shared a wall with a deserted U.S. Marshal’s office. Front and center, two townies posed with thumbs near their belt loops, clad in 10-gallon hats, flannel shirts, blue jeans, boots and spurs.

“Have you ever experienced the enthusiasm of cow boy?” asked the eloquently worded festival brochure.

Not in 28 years of living in the U.S. had I experienced a cowboy carrying an exotic South American bird. People in 1849 hadn’t, either. In fact, nobody had – ever – because this North-meets-South-squashes-Central American hybrid compressed the two continents’ 16,242,497 square miles into a single float. This was Taiwan’s take on the 900 million who called those places home. This was as “American” as it could get. Not just North American. Neither inherently Central nor South American. Not even United States of American.

All American, in the broadest and most soul-crushing sense. This was the sort of sweeping generalization I feared, and it left me envious of the 5,000 researchers living in Antarctica who weren’t subjected to a lantern interpretation.

This wouldn’t be the only time I’d face government-approved version of “American.” Each year on July 4th, many cities in Taiwan host “America Day.” Parks are outfitted with red, white and blue tents so hoards of homesick foreigners can engulf massive cheeseburgers and brats, and guzzle beer while cover bands rattle off Lynard Skynard and Grateful Dead songs. It’s a discouragingly accurate recreation of many Independence Day celebrations from my childhood.

But this first Lantern Festival was the grandest take on the stereotypes that I worried were chasing – or worse, proceeding – me every step of the way. What other judgments were being passed? Who was snickering in the crowd? How many of these Taiwanese were whispering criticisms, speculating on my agenda? Surely they could see I wasn’t wearing a cowboy hat. Clearly, I wasn’t spouting capitalist rhetoric. Could they tell that I wasn’t a … gasp … LBH?

I turned to whisk Amy somewhere less opinionated, only to realized that I was alone. Our friends all had disseminated among the crowd, and she was nowhere in sight. Maybe she had become overwhelmed by the same embarrassment I felt and was curled up in the fetal position hiding.

She wasn’t. Instead, she had met a swarm of junior high school girls who were giggling uncomfortably as they asked questions of their even-more-uncomfortable new American friend. “Where are you from?” … “Are you married?” … “Can we take your picture?”

It was that last one that caught her the most off guard.

“My picture?” she stammered. “Sure, yes, … um, … of course.”

Amy had posed for thousands of pictures while growing up. Her father had a reputation of snapping several hundred during each family vacation, and many times, his photos required her to be situated like a prop in proximity to something for scale. Barely cracking 5 feet tall, she was the perfect measuring stick to show how oversized a tree, or dog, or car, or anything imaginable might be. It was a practice that I adopted, but instead of asking her to stand in front of objects, I routinely asked her to hold things next to her head. After a while, a series of pictures developed with her holding anything from comically large Coca-Cola bottles to baby sneakers to ice-cream cones beside her face. Yet nothing in her family albums had prepared her for being stopped in a park by a group of giddy teenagers.

“Yes,” she reiterated to the girls. “Definitely. What should I do?”

“Not a picture of you,” they specified as best they could, throwing their arms around her. “With you.”

This all unfolded in the matter of seconds as they handed a camera to one of the gangly teenage boys lingering to the side. Moments earlier, I had been contemplating my place in the world, speculating whether the Taiwanese might be as prejudice against Americans as I had feared. Now, I was watching several of them with ear-to-ear grins jockey just to stand beside Amy.

When the brief madness subsided, I walked over to give her a smile of approval.

The calm was short-lived.

“Now you,” one of the girls demanded as she wrapped herself around my arm, holding on the way a child clings to a rope swing.

“Wait, what?” I said, locking fearful eyes with Amy.

The girls shoved themselves against me, hurrying Amy into the frame, too. The first girl still clung frantically to my left arm, while another hugged my waist tightly. I, however, stood there with far less gusto, my hands reaching toward the sky as though the LBH Police were off camera and just told me to “freeze.” My face was left with an idiotic daze, the same look that infants get when it’s unclear whether they are smiling or pooping. I had been in the country only a couple of days, but I could imagine the photo captions already: “My new American friends,” … and the corresponding stories, “this American guy hugged me,” … and then the eventual headlines, “Foreigners investigated for night on the town with teen Taiwanese mistresses.”

I had spent years writing newspaper headlines, and the sensationalism of my former life hadn’t totally abandoned me.

Then, almost as quick as they’d arrived, the band of high-strung teens was gone in a flash, leaving Amy and I staring at one another as if to ask, “Had that really happened?”

It had, and somewhere there’s photographic evidence to prove it.

A few months later, teenage paparazzi again would ambush Amy, this time while waiting out a violent thunderstorm with fellow motorists beneath a bridge. And this time, I kept a safe distance to avoid being spotted. As she posed, I listen with my back turned and hood drawn, lurking out of sight like a graphic-novel henchman. I knew better than to get any closer.

I’m not foolish; I am American.

user is

Email this author | All posts by user