The Error Up There

By user • May 29th, 2014 • Category: Diary The following is an excerpt from a forthcoming collection of short stories about living abroad in Taiwan.

The following is an excerpt from a forthcoming collection of short stories about living abroad in Taiwan.

A 2-mile park zigzags its way through the center of Taichung. The narrow strip of developed greenery, known as People’s Park, interlocks quads of urban development and stereotypical Taiwanese neighborhoods. It’s a far cry from the hefty real estate of New York’s Central Park or the sweeping coastline alongside Grant Park in Chicago. People’s Park runs down Taichung’s spine the way a highway divides a desert in America’s baron Southwest. It seems to go on for ages, and just before it disappears over the horizon, it breaks at a right angle, cuts back, and straightens its course.

Other cities in Taiwan have parks. Seemingly every neighborhood hides tiny swathes for residents to walk laps or push toddlers on a swing set. Larger metropolises like Taipei (DaAn Park) and Kaohsiung (Metropolitan Park) have sizeable nature areas incorporated into their infrastructures. However, no city park in Taiwan strikes the aerial profile of Taichung’s center strip.

From above, the landscape of People’s Park is plunked down, block by block, like an oversized game of dominos that plods along the city’s Y axis until there’s no forward play remaining, the only move to be a drastic change of direction. Chunk by chunk, the park climbs through Taichung methodically, never fluid, never gracefully.

At the northernmost end sits a Botanical Garden structure: an intimidating glass monstrosity housing more than 1,200 tropical plants, flanked by a 60-foot butterfly sculpture, and resembling a terror dome that a James Bond villain might construct to facilitate nuclear holocaust. On the park’s south tip is a 20-story apartment building made of white stone with a marble lobby boasting a gaudy Mona Lisa reprint, … and with a bedazzled rooftop apparently made of oversized Lite-Brite pegs. In between the park’s poles, you’ll find a performance stage known to beckon fire jugglers, a sculpture field, the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, an outdoor dance hall where senior citizens converge weekly to tango in public, the National Museum of Natural Science campus with dinosaur-themed sidewalks, a lane of shopping booths, and the patch of park used to host a 10-day annual jazz festival that attracts thousands of goers who’ve yet to realize jazz isn’t enjoyable.

At any given time, a passenger in a helicopter over People’s Park would get a unique glimpse of life unlike any other place at any other moment in Taiwan. The variety of life that this bizarre, 2-mile stretch fosters would make even David Lynch or Federico Fellini bristle with the absurdity.

It was along this park that I found myself taking a summer stroll with a dear friend, Darius. That June night, the two of us meandered south along a distinct stretch that featured a dozen coffee shops in a two-block radius.

We must have struck an imposing silhouette as we lumbered down the tree-lined walkways. Not many people in Taiwan – foreigner or local – are taller than me, standing 6’5’’ tall. Darius is one of the few folks on the island who can see the top of my head. But besides our mutual stature, the similarities end there. His lean, lengthy build has an almost Golem-like muscle ratio, making each stride feel more like slithering than walking. Whereas if I wash down just one slice of white bread with a glass of water, it packs on surplus inches of wobbly belly fat. Furthermore, I began going bald before I legally could buy alcohol, and the only thing I hate more than the daily shaving regimen is a few days’ stubble. It’s a polar opposite to Darius’ long, flowing brown locks that are perpetually tied back in a ponytail, as to not hide his skillfully groomed beard. If I look like a super-sized version of the musician Moby, then he’d be a shoo-in as the lead role in any Easter Sunday performance.

I write. He takes photos. I like board games. He’s a whiz with a video game controller. Our friendship was built, in part and despite the contradictions, out of mutual interest in getting out exploring on foot. (Even if those explorations saw Darius donning an endless array of neon-colored T-shirts, and I in standard, collared shirts that ranged from gray to charcoal gray to black to midnight black.)

It was on one of these casual jaunts – beneath the flickering glow of the stone apartment’s Lite-Brite bulbs – that we encountered a small mob of onlookers. A few dozen locals had convened in the street at the base of the housing complex. The sun had set a few hours earlier, but this particular end of the park was uncharacteristically luminescent, even for a block that regularly shined of red, pink, yellow, and green palates courtesy of the architecture’s fluorescent lighting.

As we neared the crowd, we noticed a large fire truck stationed down an adjacent alley. Its flashing red beacon no doubt was responsible for the heightened visibility. Three more police vehicles boxed in the onlookers, adding a few blinking blues and whites to the light show. The two of us stood transfixed, mesmerized by the shiny, flickering patterns the way tackle lures hypnotize fish to bite down on hooks. The difference, though, was that the crowd wasn’t lost in the colorful display that washed over them. The Taiwanese spectators didn’t care about waves of varying hues that bounced off the stone building and reflected onto the pavement en route to being absorbed in the nearby park’s trees.

Darius and I stared at them; they stared at the sky. The crowd’s collective necks all were hinged at 45-degree angles, which left their jaws hanging ever so slightly agape. Their eyes bulged but never broke the line of sight with the overhead happenings on the rooftop of the Lite-Brite building.

It’s hard to blame them for peering so intently toward the sky. Looking upward is much easier than looking toward the ground, no matter what the Sears Tower scene in “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off” implies. I experienced that lesson firsthand while visiting the city of Puli, more than a year before Darius and I joined that crowd along People’s Park’s south end.

Looking toward the heavens in Puli is a great deal different than doing so in Taichung. The geographic center of the island isn’t a crowded city by Asian standards, with only about 86,000 people throughout the entire township. Instead, Puli is bundled between rolling hills and winding mountain switchbacks.

Its topography can be credited to the proximity of the Chelungpu Fault, which cuts north to south through the middle of Taiwan. At only 62 miles long – roughly the equivalent of running the Boston Marathon 2.3 times – the fault line packs a punch of epic proportions. This was the one that recorded a 7.6-magnitude earthquake on Sept. 21, 1999, killing more than 2,400 people and causing more than $10 billion in damages. Cracks from the 921 Earthquake still crawl up building walls in Puli. Traffic still is diverted away from unstable bridges and permanently docked railroads. Boulders that rolled down hillsides are wedged over highways and threaten to tumble again if so much as a sparrow perched upon them. Sewers are split in half; construction projects remain halted more than a decade and a half later. A 21-foot waterfall was forged in the aftermath when the land cracked and runoff found a new path. A school, which crumbled overnight during the quake, remains untouched by renovations but now serves as the official 921 Earthquake Museum.

The only positive that comes from having a catastrophic fault line dividing a township like Puli is that the centuries of plate tectonics have given way to some of the island’s most beautiful mountains and chasms. This is the area’s selling point. Coincidentally, it’s also what makes selling property in the area so damn hard. Sure, Puli has a brewery. It has a monastery featuring, what was for five years after the turn of the century, the world’s largest Buddhist building. But people travel to Puli to see … well … Puli.

And the preferred way to catch a glimpse of the intoxicating landscape is from high above.

Puli seems even more peaceful from 2,300 feet. The air is fresher, and breaths come slower and easier. There’s a calmness that sets in while standing on a flat patch of mountaintop grass observing the traffic maneuvering below and peering at eye-level to distant peaks. The madness of everyday life subsides and fizzles in the breeze. Here, for now, looking down isn’t so bad.

That is, until you start to run … toward the edge of the cliff … to jump off.

That’s when looking down gets a whole lot worse.

You see, getting an aerial view of Puli doesn’t mean from the perimeter, leisurely gazing out over the township. It means that you’ve met Yuri, a South African character of legend among the expat community in Taiwan.

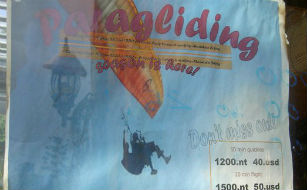

An ex-cop turned island veteran, Yuri has built a career in Taiwan by convincing countless foreigners (and locals, too) that the best way to capture a truly breathtaking bird’s eye view of Puli is to paraglide over it. It takes a person of a certain disposition to make a living strapping themselves to strangers whom they’ve known for a matter of hours – sometimes minutes – and willingly hurling themselves off a cliff with only a nylon-blend parachute between a successful day of work and a successful day of death by freefall.

Yuri is of that disposition. A betel-nut-chewing adrenaline junky, he carries the abrasive confidence of a guy who’s either done this near-death sort of thing so many times that he can handle any midflight turbulence or of a complete novice quack with zero appreciation for what terrible things would be in store with only a subtle miscue.

One was reassuring. Neither was flattering.

Yet it takes a person of an accelerated disposition to not only convince utter strangers to jump off a cliff with you, but to pay between $40-60 for the privilege to do it.

Somehow, forking over hard-earned cash to a middle-aged “flight coach” has become somewhat of a right of passage for expats throughout Taiwan’s central counties. Yuri’s stranglehold on aerial Taiwan even extended to Ang Lee’s film adaptation of “Life of Pi,” when his crew was brought onto the set to assist the director with a few overhead shots.

Looking down over places like Puli is peaceful if you can keep both feet planted on the earthquake-riddled soil. But it’s hell when looking down entails doing barrel roles, loops, spirals, and a myriad of paraglider tricks with names that sound more like sports drinks than maneuvers I’d voluntarily participate in.

Misty Flip.

Mac Twist.

Helico Rodeo.

These were the stunts I overheard Yuri’s crew mention as he gave me the safety tutorial before we got harnessed together to jump.

“Now, if something wonky happens, I’ll yell, ‘Bail.’ That’s your signal to put the evac plan into effect,” Yuri instructed.

“OK. Got it,” I replied. I certainly hadn’t “got it.”

“So, you’ll pull this, put your arm here, spin it like this and release.”

I couldn’t recall ever hearing somebody speak so quickly. Either I was an idiot incapable of keeping up with simple directions, or he was rambling at an auctioneer’s pace. Truth be told, the safety procedures were lip service. If there were a midflight emergency, no amount of arm-twisting or clip-releasing could save two grown men in a head-to-head battle with gravity.

“Got it,” I mumbled again. I still hadn’t “got it.”

That less-than-authoritative declaration was Yuri’s cue to strap his chest to my back and sprint toward the ledge.

It’s a good thing that the parachute stretching behind us gave such resistance. We had to lean back while scampering forward. I’m quite a bit taller than the energetic daredevil who was tethered to me, and had I been able to angle myself forward, I might have jostled his confidence by giving the little fellow a piggyback ride.

Yet, we hit no snags – literally or figuratively – as the wind filled our chute and our feet gradually lifted off the grass. We were carried upward quickly. With a few tugs of the steering, Yuri had us spiraling back over the launch pad where my friends stood staring up at us. Their necks were hinged at 45-degree angles. Their mouths hung slightly agape.

For most of the afternoon, that had been my position. I’d watched friend after friend – five in total – stand butt to nut with Yuri and dive into the wild blue yonder. It all had looked so peaceful from the ground. The paragliders’ loops before had seemed effortless. The spirals had looked graceful. Even the takeoff plunges appeared to be a natural process when my vantage point had my heels dug into the earth.

That’s not the case while flying.

There’s no breeze in your hair at 2,300 feet. It’s a hurricane gust smack dab in the face. There’s no bird’s-eye view to be had with eyelids clenched shut. Worldly sounds get fainter a half-mile in the air, and the higher you soar, the only audible noise is the terrifying echo of Darth Vader-like breath inside a helmet. But just as I began to reconcile airborne feelings of abandonment – the cold sweat giving chills with each gust of wind – Yuri piped up to remind me that I wasn’t alone. In fact, far from it. There was a middle-aged South African, who’d just chugged a Red Bull and popped a fresh betel nut, still strapped to my back.

“Let’s have some fun,” he shouted into my ear.

These are the type of threats you don’t hear from the ground while you’re looking upward. But they ring loud and clear in while soaring over buildings, streets and a wild pack of family dogs.

“Got it,” I agreed. I definitely hadn’t “got it.”

A part of me wanted to “get it” because it was the final flight of the day. After Amy had excitedly – and proudly – volunteered to fly first, the bar had been set for each confident voyager that followed. So if I didn’t “get it,” I’d be the only passenger who chickened out of the acrobatics. Another part of me wanted to “get it” to atone for a teenage mishap involving a 1-pound bag of Skittles, a ride in a glider plane, and a large amount of multi-colored vomit.

Taste the rainbow.

“Here we go!” Yuri warned.

This time, I said nothing. I was tired of lying. Besides, it’s hard to speak with a locked jaw.

Those on the ground looking upward had no idea of the chaos overhead. The emotions. The panic. The threats of having “some fun” that were being veiled as opportunities. I sure did, though, as I tilted my head and forced open my eyes to glimpse the world below. My feet dangled next to Yuri’s in an oddly romantic manner as the paraglider tipped sideways, so we could swoop above a group of college-aged locals having a picnic lunch along the mountain rim.

“Hey, baby!” Yuri heckled down to a few of the women. “Ow! Ow!”

I couldn’t escape. I literally was tied to this guy. Several stainless steel hooks, a few belts and a total dependency on his piloting meant I couldn’t get away from this catcalling jockey. Thankfully, the women didn’t respond. They just looked up at us peacefully, with their necks at 45 degrees and their mouths slightly agape. I’m certain they pitied us. How could they not? They were lounging casually on the turf while we blitzed overhead like a cyclone of fear and sexual aggression.

Looking up always is more peaceful than looking down. Whether it’s while swaying a paraglider to chase a flock of birds or while standing along a park amid a crowd of bystanders during a mid-summer’s evening, people looking upward have it much easier. Looking down is scary because, chances are, you’re not supposed to be wherever you’re looking down from. People aren’t meant to get fastened together and jump off cliffs. People aren’t meant to bare their uncertainties and loom over a mob of gawking strangers.

This grew all the more evident as Darius and I approached the dozens of onlookers who stood entranced with their eyes pointed upward at the Lite-Brite building on People’s Park’s south end. It didn’t take long, however, until he and I had fallen victim to the same open-mouthed stares that we had wondered about moments earlier.

“What do you think it is?” I asked.

“Maybe a jumper,” Darius replied with a hint of curiosity in his voice.

“No way!” The anticipation bubbled the way I’d react if a shop clerk revealed that an A-list celebrity bought the exact same pair of shoes last week.

“Makes sense,” he surmised. “Cops. Fire trucks.”

By this point, we both had broken our upward ganders to peruse the park level for clues. None was more evident than the humungous landing pad inflated on the street.

“Definitely a jumper,” I said. “But I don’t see anyone.”

“Keep looking.”

Darius and I scanned the building’s exterior, taking note of shadowy figures on window ledges, looking for movement atop the flickering rooftop, ironically scouring for any signs of life.

Minutes passed. We saw nothing. Occasionally, more bystanders would trickle in to replace those who’d grown tired of waiting on a fool’s errand and abandoned their posts. The newbies’ fresh excitement always reinvigorated the group who’d grown weary with no action. Police and fire crews interchanged, and more barricades were erected to keep the anxious mob at bay.

“I don’t see anything.” The disgust in my voice was palpable. “I wish something would happen.”

A few more minutes passed.

“If he hasn’t jumped by now, this never is going to happen,” Darius sighed.

Several more minutes went by, and we’d each texted our significant others to divulge the once-in-a-lifetime chance they were missing.

As even more time passed, there was no noticeable action from above. Yet, we all kept our eyes fixed on the rooftop ledge.

“Whaaaaat are ya doin’?” a voice rang out from behind me.

In all of the excitement, I failed to recognize that Amy had crept up beside us. She asks that question often, and I could tell by the elongated first word – “Whaaaaat” – that this time it was out of sheer bewilderment, as if she’d stumbled onto a coworker meticulously smearing peanut butter onto a magnifying glass.

Amy didn’t expect a logical answer.

“We’re waiting to see if someone is going to jump,” I said.

Another moment passed. Some people in the crowd snapped photos.

“Why?” she bemused.

“Why what?” I stalled. The truth was that there wasn’t a good reason. But if bad TV sitcoms had taught me anything, it’s that a husband can buy a few extra seconds to think of an excuse by repeating his wife’s question.

“Why do you want to watch a guy jump off a building?”

“Must you assume it’s a guy? Depression is gender-neutral.” I was really grasping at straws now, further stalling by playing the sexism card. Amy didn’t take the bait. She just looked up at me in silence while more neighbors joined the increasingly impatient mob.

Why did I want to see a stranger, struggling with something, plummet to his (or her) death? There was no real answer besides that of having the opportunity. Boredom? Curiosity? Nothing I concocted sounded remotely justifiable. So I looked down at Amy standing next to me – it was much harder looking down than up – and was honest.

“I don’t know.” It rolled off my tongue a bit like a confession, a tad like a revelation.

She’s a greater moral compass than I tend to admit. Imagine what it feels like to look down over a mob of strangers who’d like nothing more than to see you jump to your demise. Pointing at you. Taking pictures. Laughing and imploring their friends to swing by and check out the free show. Who’s the troubled one? Who needs help?

“So let’s go,” she said. “There’s nothing to see here.”

With that, we left. Darius followed close behind after overhearing the full exchange. Without realize it, we had morphed from compassionate adults into medieval townsfolk entertained by public executions. The both of us sauntered away from the horde with our heads hung embarrassingly low.

Looking down always is more difficult.

user is

Email this author | All posts by user